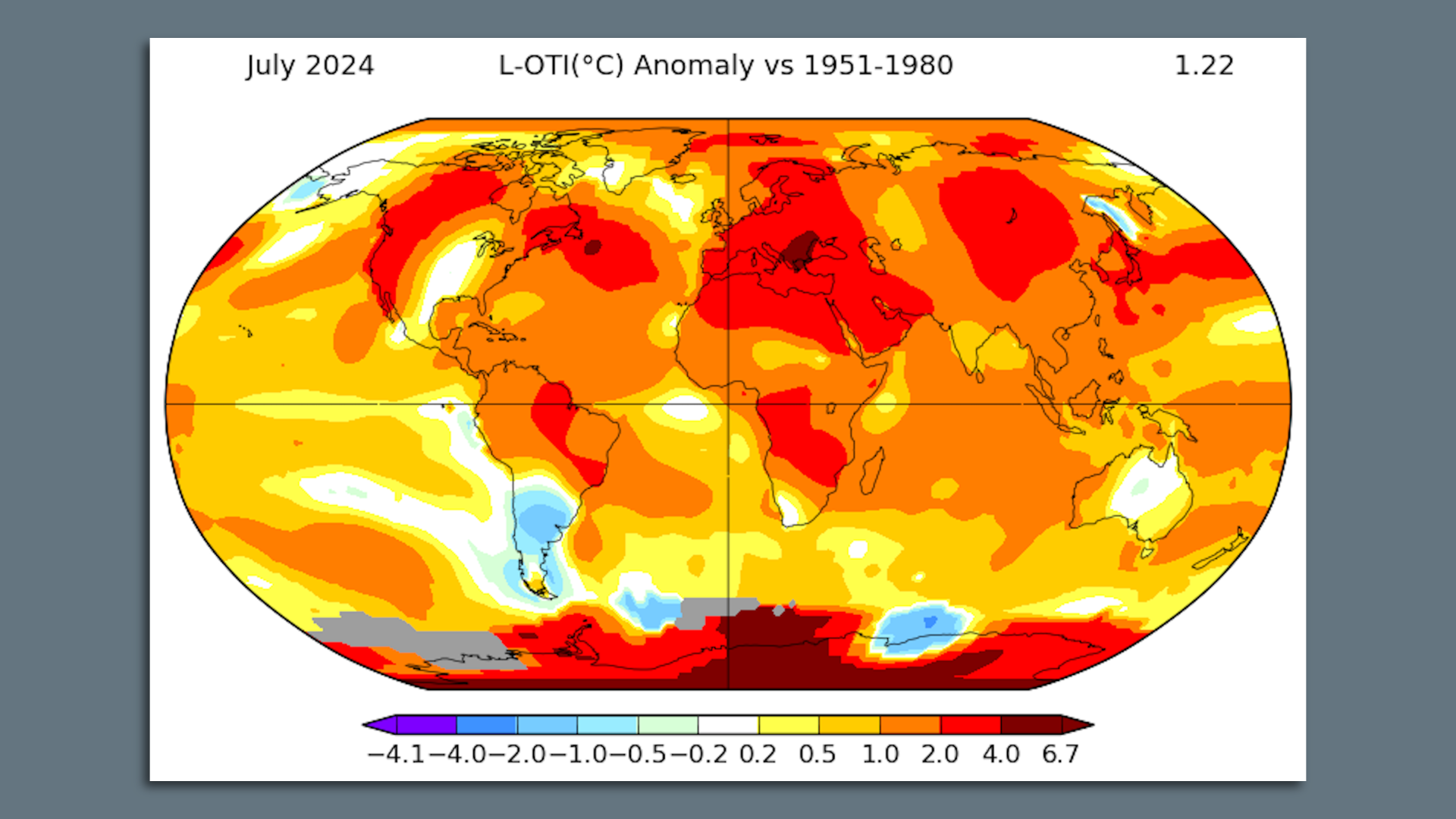

Map showing global average surface temperature departures from average during July 2024 in NASA’s data set. Image: NASA

Additional global temperature data is in, and it shows July was ever so slightly warmer than the previous record, which occurred last year.

Why it matters: Month-to-month climate fluctuations face more scrutiny this year following 2023’s record warmth that researchers still have not fully explained.

- The expectation of many climate scientists is that the unsettlingly rapid warming last year would soon return to the pace of the past decade.

Zoom in: The new July report comes from NASA, and it differs slightly in its ranking from European data released last week.

- That calculation showed a second-warmest July and an end to the year-plus streak of record warmest months. But NASA’s brings the heat record streak to 14 consecutive months.

- The lack of significant cooling in NASA’s records compared to July 2023 is noteworthy but not a warning that we’re still heating up at last year’s rate.

By the numbers: The July data signals that 2024 is likely to be slightly warmer than 2023, setting a milestone for the warmest year.

- Gavin Schmidt, who directs the NASA lab, wrote on BlueSky that the odds of a new hottest year range from 88% to 98%, depending on whether a La Niña event is underway in the tropical Pacific.

- Others have placed the odds in a similarly high range.

Between the lines: Schmidt also noted that the slightly hotter July is still following a trend away from 2023’s anomalous warmth.

- “The bottom line is that 2024 temps are much more in line w/expectations than 2023, lending more weight to the notion that 2023 was more blip-like,” he wrote.

- Research continues into why last year’s global average temperatures were so unusually hot.

Yes, but: While cooler-than-average ocean temperatures are in place in parts of the tropical equatorial Pacific Ocean, the needed air and ocean elements for a La Niña climate cycle to occur are not yet present.

- Such phenomena tend to reduce warming rates, but recent NOAA outlooks have pushed back the starting period for the next La Niña closer to late fall, while also reducing its likely peak intensity.

- This may make any La Niña-related, temporary brake on global warming particularly ineffective.