Wending its way from the Olympic Mountains to the Strait of Juan de Fuca, Washington’s Elwha River is now free. For about century, the Elwha and Gilnes Canyon Dams corralled these waters. Both have since been removed, and the restoration of the watershed has started.

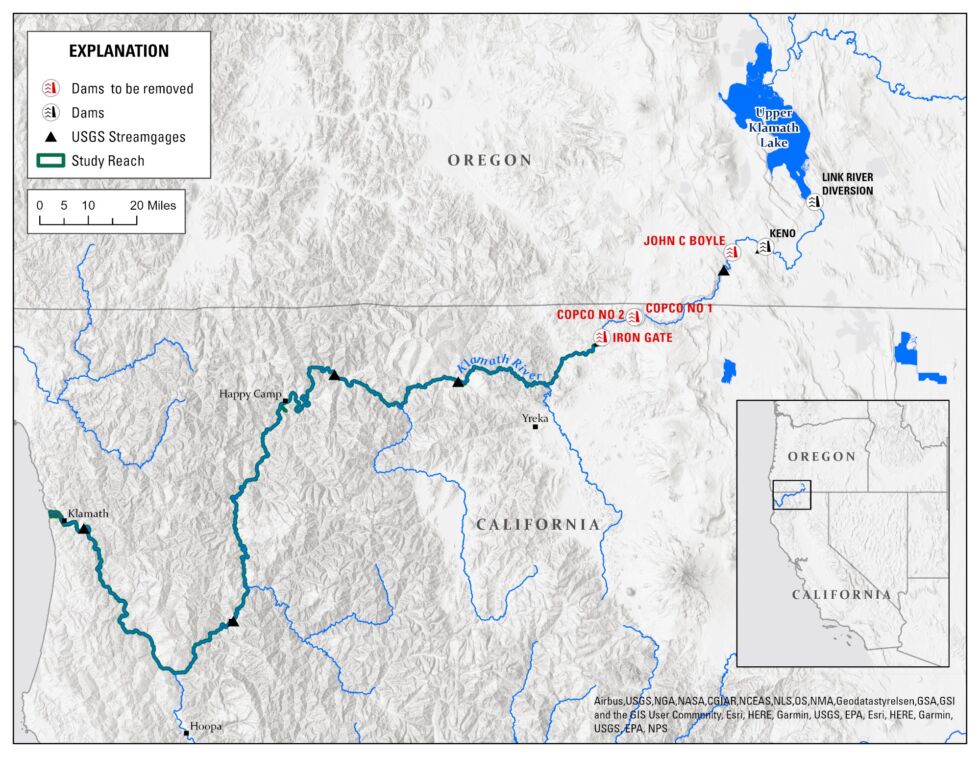

The dam-removal project was the largest to date in the US—though it won’t hold that position for long. The Klamath River dam removal project has begun, with four of its six dams—J.C. Boyle, Copco No. 1,?Copco No. 2, and Iron Gate—set to be scuppered by the end of the year, and the drawdown started this week. (In fact, Copco No. 2 is already gone .)

Once the project is complete, the Klamath will run from Oregon to northwestern California largely unimpeded, allowing sediment, organic matter, and its restive waters to flow freely downriver while fish like salmon, trout, and other migratory species leap and wriggle their way upstream to spawn.

Across the US, dams are being removed for various reasons. Many are simply old. “They’re in rivers beyond their designated life span,” said Lucy Andrews , a doctoral student at the University of California, Berkeley, who studies water resource management. “They have a high potential of failure, particularly when climate change is considered.” In other words, these dams weren’t designed for today’s capricious precipitation regimes. Other dams no longer function in the way they were designed, said Jonathan Warrick , a coastal geomorphologist with the US Geological Survey.

Removal can also reverse ecological damage that, in the western US, often harms migratory fish but can also cause problems for other sensitive species and ecosystems. In addition, dams “have displaced tribal nations from their lands and severed connections to culturally important waterways and species,” Andrews said, speaking specifically about California. “In these contexts, dam removal can actually be an important step toward repair.”

Taming the water

Dams, both large and small, serve various purposes, said Andrews (large dams are mostly those taller than 15 meters—roughly the height of a four-story building).

“Many dams were constructed in the eastern states for mills and power generation,” said Warrick. Most of these dams were relatively small, but after World War II, large dams proliferated across the West. Today, US dams control floods, generate hydroelectric power, and store water for municipal or agricultural use, he explained. “Most dams are built to do a little bit of each.” Recreation also factors into cost-benefit analyses for existing dams, Warrick said.

The Glen Canyon dam impounds the Colorado River in northern Arizona and is among the larger of the “large” dams in the US, with a height of 220 meters (710 feet).

But “dams disrupt a number of things through the river corridor,” Warrick said. “Dams capture any sediment that is flowing downstream.”

As the upstream river empties into the reservoir, it loses energy, which governs its ability to hold sediment. A delta of sand and gravel propagates at the upstream side of the lake that forms behind a dam—far away from the dam itself. Fine and muddy sediment may drape the rest of the reservoir. In some cases, the reservoir fills completely with sediment, turning the dam into waterfall, as has happened at Southern California’s Rindge Dam . (These days, there are ways you might get sediment out of reservoirs, ranging from dredging and hauling to building sediment bypass tunnels that use gravity and the river itself to do the work.)

On the downstream side, rivers are then starved of sediment, Warrick said. When water is released from its reservoir, it’s often “hungry .” Flowing water can carry a certain amount of various-sized sediment, and when it lacks it, the water will erode the river’s beds until it carries the right amount. This erosion downstream of a dam can strip the bed of sand and gravel, resulting in a stream bed armored in much coarser rock, Warrick said. Think of cobbles and boulders instead of beachy (sand) bars. Or the river may completely carry away any existing bars and beaches. Somewhat lazy streams may morph into straight, narrow channels that incise down, destabilizing banks.

This sediment starvation also matters along the coasts. For example, the tribe living on the Elwa River delta “were experiencing—on average—a meter of erosion of their lands per year,” Warrick said. Where cows once grazed, farmland once produced food, and children went clamming (clams prefer sand, not cobbles), the land and habitat were gradually lost to the sea. “Since those dams have come out, we’ve seen this massive expansion of the coastal lands and wetlands,” he said.

Enlarge / These satellite images show the evolution of the shoreline around the mouth of the Elwha River before, during, and after dam removal between 2011 and 2017. Water woes

Not only do water regimes change after the emplacement of a dam, but so too does temperature, oxygen, and water quality. A reservoir’s surface waters will warm as the lower layers remain cool. Depending on lake levels, the water exiting the dam via the outlet might be unseasonably warm or cold. “For example, on flood-regulating dams, outlets are located lower in the dam, which typically is where the heavy, hypercooled water is found,” said Desirée Tullos , a water resources engineer at Oregon State University. “So, it will release hypercooled water during the summer and warmed water in the fall, both of which are bad for fish.”

Stagnant reservoir water can also cause cyanobacteria to thrive, Tullos said. This is a problem in the Klamath, where yearly cyanobacteria blooms produce toxins . Plus, as cyanobacteria die, their decomposition depletes oxygen, Tullos explained. The release of anoxic reservoir bottom waters can compound oxygen depletion downstream, though this effect tends to be short-term, she said.

The toxicity particularly impacts those who live near the river—especially members of Native American tribes who can no longer fish or swim. These losses negatively affect both physical and mental health, said Brook Thompson , a Yurok tribal member and doctoral student at the University of California, Santa Cruz. “Water quality and amount also affect cultural aspects of life.”

Ecological effects

Dams are physical barriers for most migratory species in the fluvial corridor, Warrick said. This includes not just salmon but also creatures like lampreys—primitive, jawless fish with toothy mouths that suction to their hosts.

Solutions for migratory fish exist, like fish ladders or fishways, which provide a detour in the form of ascending pools. In other cases, people ferry salmon upstream. For instance, efforts to transport juvenile migratory fish via barges began in the Columbia River as early as the 1950s, said Toby Kock , a USGS Research Fish Biologist. That practice is still occurring today . “Developing and improving methods for providing passage for aquatic species at dams is a very active topic worldwide,” Kock said, because dams limit fish access “to critical high-quality coldwater habitat located in the headwaters of many rivers.”

John Day Dam fish ladder on the Columbia River is just one example of the ways to get salmon and other migratory fish upstream to spawn.

Army Corps of Engineers

When dams are in place, few logs, sticks, and trees flow downstream, instead ending up stuck in a reservoir. “Large wood pieces are really important in terms of habitat,” Warrick said. Fish and birds along riparian corridors prefer complex settings. “Birds like to sit on nooks, and fish like to be in little holes, and trees and wood make those habitats richer.” When dams are removed, more wood enters the river corridor, and ecosystems become better for it.

Taking down a dam

The vast majority of removed dams have been small, either check dams or those used for water diversions, said Warrick. Little dams can be taken down by a small team with a backhoe, Tullos said. “And there’s virtually no environmental impact.” This has been shown in study after study .

“There’s only been a few really large dam removals,” said Warrick, and these projects require extensive planning. “Each dam removal is very unique,” Thompson said.

In general, large dam removal begins by draining the reservoir while doing something about the stored sediment. As lake levels recede, dam and facility removal commences, as does river restoration.

For example, when the Glines Canyon Dam on the Elwha was removed, the reservoir was drawn down to the spillway gates, allowing deconstruction of the exposed lip of the dam. Then, the remaining dam was notched on alternating sides, with each notch functioning as a temporary spillway to drain the reservoir while encouraging sediment from the upstream delta to move closer to the dam. Once the delta was fully redistributed, the remaining dam was removed as restoration began .

Elsewhere, like in Southern California, “[the] hydrologic regime is mostly no flow to low flow,” Warrick said. Storms that are strong enough to move significant quantities of sediment only come along every few years, which means that planning becomes a difficult engineering problem. For instance, when the San Clemente Dam on the Carmel River was removed , the entire river was rerouted to permanently store the impounded sediment because of concerns that if it was released, it would build up on the flood plain and increase flood risk to structures there, Warrick explained.

This map shows where the Carmel River was rerouted during dam removal, which left most of its reservoir sediment in place.

Freedom

When the main Elwha dam removal project was being planned, scientists calculated that if you dredged the sand and loaded it into trucks, those trucks would be backed up from the Elwha Dam all the way to Boston and back, Warrick said. Though the Klamath River dam removal project will outrank the Elwha as the world’s largest, its impounded sediment is not nearly so voluminous and will instead pose different problems.

On January 9, 2024, drawdown began. A low-level outlet was opened on Iron Gate Dam, and the river will turn to “chocolate milk,” she said. Scientists hypothesize that minerals and metals stored in the reservoir’s sediment will oxidize as they’re released, further contributing to oxygen depletion. “The respiration and decomposition of old dead algae that is at the bottom of the reservoir,” she said, “probably won’t have a meaningful impact until summer.”

However, the winter timeline should help because high flows can efficiently flush the sediment out, Tullos explained. And it’s also a time when most sensitive fish aren’t present in the river. “The drawdown is timed to minimize the impact on fish.”

This project, though, is not an attempt to answer a colonial project with yet another. The Karuk, Klamath, Hoopa, and Yurok tribes have traditionally fished the Klamath River. “The tribes have had a major leadership role,” Tullos said. This has been true throughout the process and will continue with restoration, which is one of the biggest costs of large dam removals.

Tribe members, including Thompson, are collecting native seeds and will be propagating these plants. “If we do not do native seed replanting, it will 100 percent get taken over by invasive species,” she said. “With the drawdown, it’s such a great opportunity to be able to give these native species a chance.”

The Indigenous perspective may be different from how many view resources like water. “A lot of Americans are running on the assumption that resources are here for us to use,” said Thompson. “That’s the basis of a lot of our water laws.”

But “a Native American perspective is that we are living in a relationship with these elements, rocks, fish, plant species,” she said.