|

|

|

Falling Gasoline Use Means United States Can Just Say No to New Pipelines and Food-to-Fuel Janet Larsen |

Earth Policy Release |

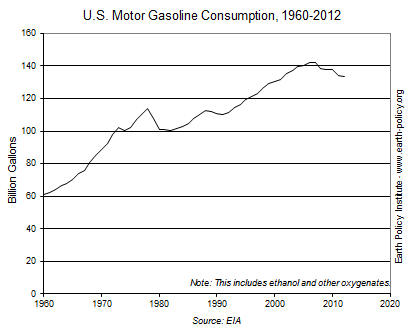

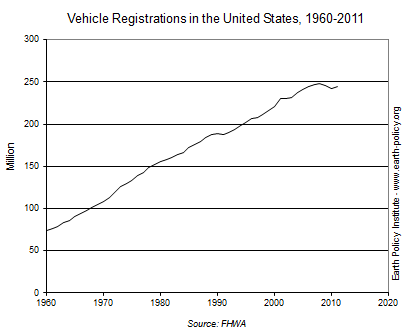

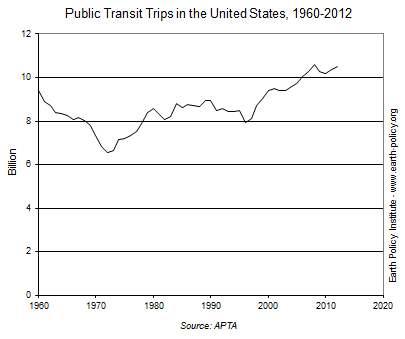

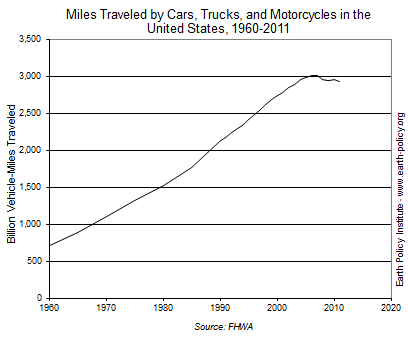

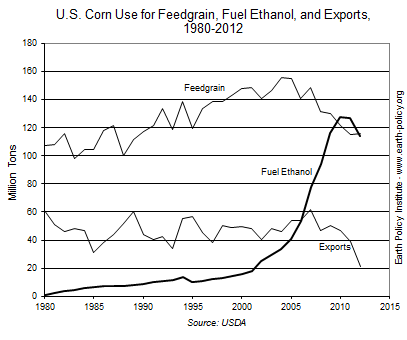

Freeing America from its dependence on oil from unstable parts of the world is an admirable goal, but many of the proposed solutions—including the push for more home-grown biofuels and for the construction of the new Keystone XL pipeline to transport Canadian tar sands oil to refineries on the U.S. Gulf Coast—are harmful and simply unnecessary. Gasoline use in the United States is falling, and the trends already driving it down are likely to continue into the future, making both the mirage of beneficial biofuels and the construction of a new pipeline to import incredibly dirty oil seem ever more out of touch with reality. U.S. motor gasoline consumption peaked at 142 billion gallons in 2007. In each year since, American drivers have used less gasoline. In 2012, gas use came in at 134 billion gallons, down 6 percent off the high mark. Three trends underlie falling U.S. gasoline use: a shrinking car fleet, an overall reduction in driving, and improved fuel efficiency. The number of registered vehicles in the United States rose rather steadily from 1945 to 2008, when it topped out at close to 250 million and then abruptly changed course. As the economic recession hit, new car sales in the United States fell from more than 16 million in 2007 to below 11 million in 2009. For two years, scrappage exceeded new purchases, causing a contraction in the overall size of the fleet. Even with a rebound in sales to nearly 15 million vehicles in 2012, the days of annual sales exceeding 17 million—as seen through the early 2000s—are likely over. (See data.) The car promised mobility, but in urbanizing communities it instead brought traffic congestion and air pollution. With four out of five Americans now living in urban areas, private vehicle ownership is starting to lose its allure. This is particularly true among younger people, who are readily embracing mass transit and the car-sharing and bike-sharing programs that are popping up in cities around the country. Fewer than half of American teenagers ages 15 to 19 have a driver’s license, a share that has been falling over recent decades as states have tightened restrictions and as socialization patterns have shifted from cruising the streets to cruising the Internet. Retirees also tend to drive less; as the baby boomers retire, more people will be putting away their car keys. As gasoline prices have risen, private vehicles have traveled fewer miles and public transit ridership has increased. Not only are there fewer vehicles traveling fewer miles on U.S. roads than there were just five years ago, but new cars today can drive farther on a gallon of gasoline. This will soon accelerate: after more than two decades of near-total stagnation, in 2011 the Obama administration increased fuel efficiency standards for cars and light trucks from an average of 27.5 miles per gallon in 2008 to 54.5 miles per gallon by 2025. In addition to the technological changes that can improve the fuel economy of conventional vehicles, new plug-in hybrid electric cars and fully electric vehicles use far less gasoline or even do away with it entirely. Somewhat counterintuitively, falling gasoline use is at odds with the federal mandate to use more renewable fuel. Under the 2007 Energy Independence and Security Act, the Renewable Fuels Standard (RFS) requires blending increasing volumes of ethanol into the U.S. gasoline supply, regardless of how much gasoline is needed. In 2012, U.S. distilleries produced 13 billion gallons of fuel ethanol, almost entirely from corn. Ethanol accounted for nearly 10 percent of the U.S. gasoline supply. The 2013 requirement for 13.8 billion gallons is likely to go beyond the 10-percent threshold of what can be blended into gasoline and still be used in older vehicles without risking engine damage and voiding warranties. Furthermore, the RFS requires a growing share of the renewable fuel to come from cellulosic non-food biofuels, yet these have not become economical to produce on a meaningful scale. The increasing production of corn-based ethanol has pitted food use against fuel use, with the unfortunate result of higher food prices. As drought in the U.S. Corn Belt shrank harvests in 2012, corn prices spiked to an all-time high. U.S. corn carryover stocks fell to 6 percent of use in 2012, a historic low. Still, more than 40 percent of the 2012 corn harvest will likely go to fuel cars. While corn exports from the United States were down in 2012, gasoline exports were up. Higher domestic production and reduced demand allowed the United States to export more oil products than it imported for the second year in a row—after more than six decades of being a net importer. The United States is still a net importer of crude oil, though. Instead of necessarily allowing more gasoline to reach U.S. markets, the proposed Keystone XL pipeline would bring the carbon-intensive Canadian tar sands oil closer to Gulf Coast export terminals for easier access to international markets. A March 2013 report by the National Research Council describes policies and technologies that would allow the United States to cut its gasoline use 80 percent by 2050. Yet the data they used on the distances being driven only went through 2005, missing the recent drop, and many of the social trends that are starting to drive down car use were not incorporated. These trends are important to consider when envisioning energy and transportation policies for the future. This means rethinking mobility beyond private automobiles. And putting a price on carbon to encourage powering the cars still on the roads with carbon-free wind-sourced electricity can help move the United States beyond ecologically disruptive false solutions that raise food prices and further destabilize the climate. |

|