By Kristin Toussaint, Fast Company

PacWave handled all the permitting and construction, so wave energy developers can test their tech in the ocean.

The Offshore Support Vessel Nautilus is seen off the coast of Oregon near Newport. [Photo: Ellie Lafferty/Oregon State University]

One of the biggest challenges with renewable energy is its inconsistency: clouds might block the sun one day, or winds die down. But there are always waves in the ocean—even on calm days, and even at night. Harvesting wave power, though, has been historically difficult. Now, a project off the coast of Oregon hopes to change that, by providing a testing ground for wave energy to become a reality.

The wave power industry is about 20 years behind wind power, says Burke Hales, a professor at Oregon State University and the chief scientist on the PacWave project, the testing site seven miles offshore in Newport, Oregon. And one big reason why is because of how challenging it is to test the technology.

It’s difficult to build in the ocean—both in terms of the physical construction, and the permits and approvals needed. “If you’re trying to build a wind turbine, you need property, but you don’t have to charter a vessel or figure out how to build an anchoring system to keep that thing from drifting off,” he says. “It’s just much easier to do a land-based test than it is to do an ocean test.”

When wind energy was still nascent, developers tried all different designs. The wind turbine we see everywhere now, with its three rotor blades, was a result of that real-world testing. When it comes to wave power, there’s a lot of diversity in the devices that currently exist—but the industry has yet to test them all and determine what works best. “You can engineer a system that produces lots of power in a theoretical environment,” Hales says. But putting that system in the actual ocean, with all its variety in waves and conditions, is different.

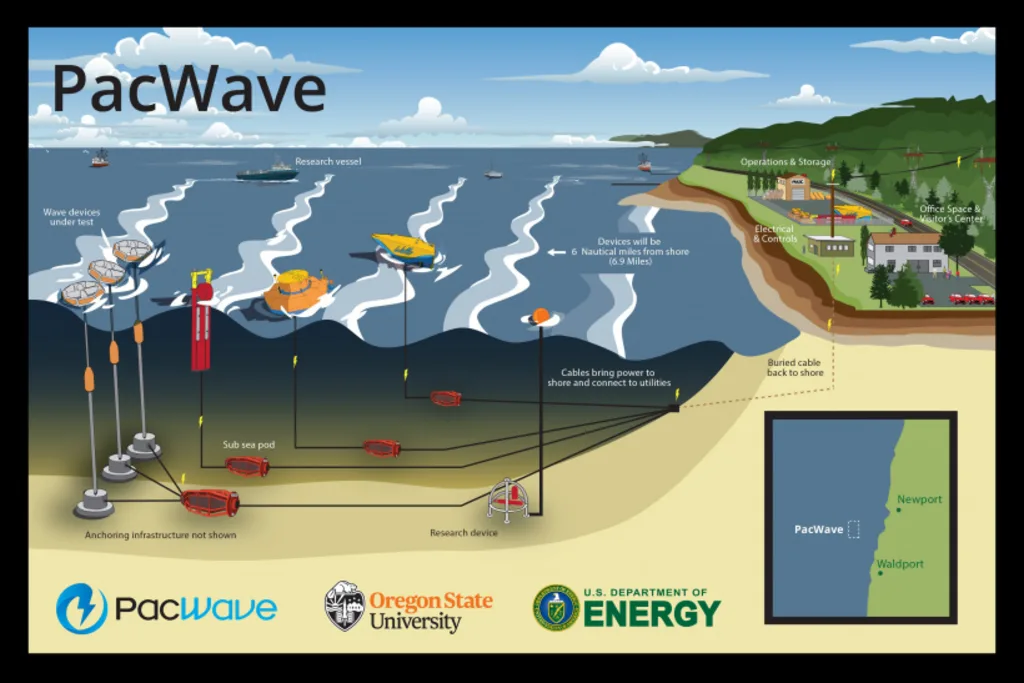

That’s where PacWave comes in. The project is a 2-square-mile test site in the Pacific Ocean for wave energy developers. It includes four independent cables buried below the seafloor, which connect onshore to the local utility grid, and to a PacWave facility that collects data. Those cables are five megawatts each, for a total peak capacity of 20 megawatts of power—enough to power a couple thousand typical homes.

PacWave has been in the works for years. Hales joined the project in 2017, and says it predated him by a decade. In that time, experts have been working on all the complicated construction and permitting to build the facility, install the under-sea cables, and bury conduits beneath the beach in such a way as to minimize environmental disruption. The project has already won an engineering award for how it buried those conduits. To get to this point where the site is almost ready for testing, PacWave had to complete a 2,000-page permitting document, working with the EPA, fisheries, state agencies, and more.

Hales emphasizes that PacWave and Oregon State aren’t the ones figuring out how to best harness energy from waves. They’re just providing the facility for researchers and developers. “It’s like, the people who built the opera house don’t know how to sing,” he says. “[PacWave is] a facility that supports the people who are working in this sector. And that’s really been the bottleneck that’s kept wave energy from moving forward for the last couple of decades.”

Until PacWave, he adds, the opportunity for a wave power developer to test in a fully regulated, grid-connected facility in the ocean has been almost impossible. (Some developers, like Eco Wave Power, have built small facilities, but PacWave will allow for more developers to test their technology without going through their own permits and construction.)

The testing site is expected to be open for business in June 2025. Not all wave power devices that will test there will connect to the grid, but the first to do so, CalWave, will be up and running at the site in the summer of 2026. Several of PacWave’s clients are funded by the Department of Energy.

Though the testing is happening off the coast of Oregon, wave power isn’t the best fit for that region at the moment. Oregon is unique in that its wholesale electricity prices are low—about 3.5 cents per kilowatt hour—and wave energy devices can’t yet match that cost. Where Hales sees wave power really working is in places like Kodiak, Alaska, where solar power isn’t viable throughout the whole year, and where communities currently bring in lots of diesel to run generators during the dark months.

The testing at PacWave, though, could pave the way for wave power to join wind and solar in our national energy mix. Scientists project that waves could supply 20% of U.S. electricity. “It’s not an alternative—It’s an augmentation,” Hales says. “It’s part of a diversified portfolio in renewables.”